The Challenge of Misused Tongues: A Survey

Now back to our main topic — which tongues count? (See Pt.1 for what “tongues” means.)

My focus here is on the secondary function of tongues in Acts, but that one that is crucial socially for Pentecostals, not only doctrinally, but in practice. Pentecostals rely on this secondary function of tongues to serve at least two practical communal purposes. First, tongues tangibly identifies who has had the experience of Spirit baptism. Second, in some Pentecostal denominations (e.g., the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada [PAOC], the Pentecostal Assemblies of Newfoundland and Labrador [PAONL], and the Assemblies of God, USA [AG]), the experience of speaking in tongues is required to be eligible for ministerial credentials.

Tongues has, then, taken on some extra-biblical (but not non-biblical) functions socially: 1) it functionally identifies not only who has had a particular experience with the Spirit, but also who is truly a participant in the Pentecostal church community (although this depends on how much a given local church emphasizes tongues), and 2) who may occupy a decision-making leadership role in some denominations.

In an online discussion with fellow PAOC/NL credential holders, I raised a question that a friend of mine (non-credential holder) about the misuse of tongues. (It’s actually his question that prompted this entire blog series.) He had come across an article in the Washington Post about former US President, Donald Trump’s Pentecostal and charismatic Christian supporters. In a conference call with Trump, some of these followers began praying in tongues on the call. My friend’s question was this: What is the source of those tongues? Is it the Holy Spirit (which would perhaps imply an endorsement of Trump), is it demonic imitation of tongues (which might imply that Trump’s followers were demonically-influenced), or something else?

This isn’t a question arising due to this story. It’s also one that we could raise simply from Paul’s discussion in 1 Corinthians 12 – 14, especially 14:23, 27-28. There Paul asserts that it’s possible to use tongues inappropriately in a corporate worship context. Unless interpreted for the listeners, tongues should be used as a private communication between the believer and God. This implies that inappropriate tongues are not God’s will, and therefore not the direct intention or activity of the Spirit. If not, then, what is the source of the tongues?

23 So if the whole church comes together and everyone speaks in tongues, and inquirers or unbelievers come in, will they not say that you are out of your mind? …. 27 If anyone speaks in a tongue, two—or at the most three—should speak, one at a time, and someone must interpret. 28 If there is no interpreter, the speaker should keep quiet in the church and speak to himself and to God.

1 Corinthians 14:23, 27-28

So, while the Trump scenario prompted the question, this is not a question new to the twenty-first century; first-century Christians could equally have asked: When there is sufficient reason to doubt that tongues speech is the direct intent and activity of the Spirit, what is the source of the tongues?

Sources of Tongues: Options

I took this question to my fellow credential holders to see what they would say. The options that came up during our online discussions included the following:

- Maybe tongues is directly and supernaturally God-given at Spirit baptism, and the person retains the ability to speak in tongues at will (implying that the tongues may not always be directly influenced by the Spirit).

- Maybe tongues not directly caused by the Spirit is of demonic origin, a nefarious vocal forgery.

- Maybe the tongues is merely an intentional or unconscious mimicry of what a person has heard others doing. This would not preclude it being used by the Spirit.

- Close to #3, maybe tongues speech is a human ability that can be learned, not necessarily by direct mimicry, but either by indirect imitation of the type of speech activity they are hearing, or prompted by the Spirit (such as having thoughts that seem to be unknown sounds or language, and attempting to speak these out), or prompted by demons (Pentecostals would assume this would be a non-Christian context). While the impetus for the tongues could have different sources, then, in this case the capacity resides in any human (assuming adequate brain functioning). Tongues speech is not a “supernatural” ability, but may be prompted by or used by the Spirit.

When there is sufficient reason to doubt that tongues speech is the direct intent and activity of the Spirit, what is the source of the tongues?

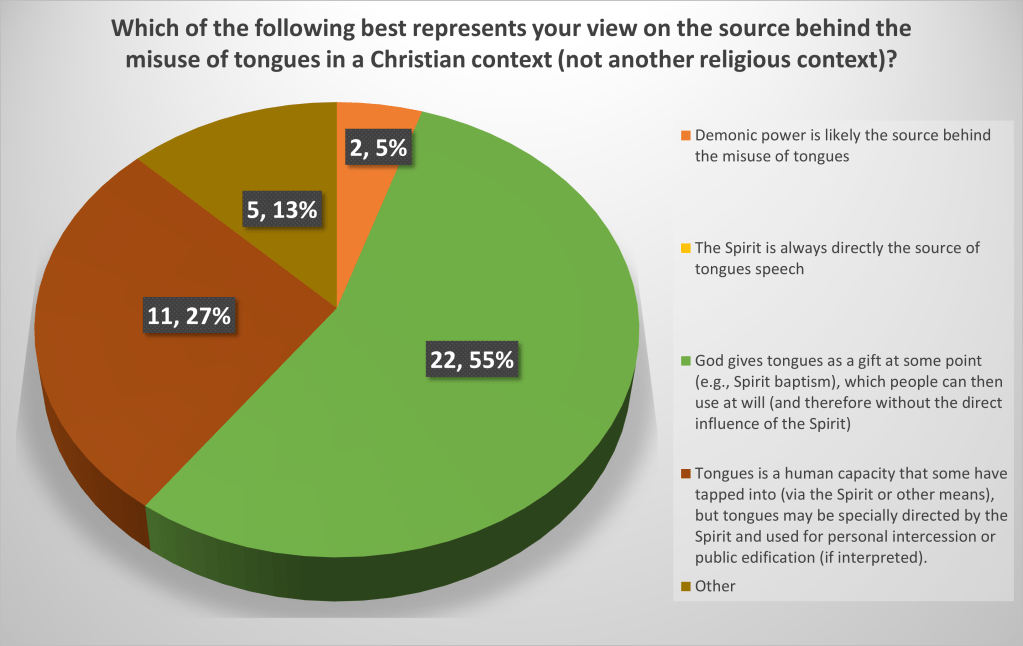

After some back-and-forth online conversation with my fellow credential holders, I created an anonymous just-for-fun survey on the topic. I wanted to discover what others were thinking about tongues, and especially what they thought about what counted as authentic (i.e., directly Spirit-directed) tongues. I asked three questions, and had forty-one ministerial credential holders respond. Not as many as I’d hoped, but enough for some diversity to emerge. The results are below (I hope these images will be clear enough).

The source behind misused or inauthentic tongues

Here the majority (55%) looked at tongues as an ability given supernaturally by the Spirit at some point (presumably at Spirit baptism). The speaker could then use the tongues gift at will, which might mean that the tongues spoken may or may not be in accordance with the Spirit’s will at any given moment. Neither would the Spirit, I’m assuming, need to be directly involved. This might mean that at times the tongues-speaker is aligned with the will of the Spirit and other times not, which would provide a good explanation for how tongues could be misused (such as in the case involving Trump’s charismatic followers, if one is not inclined to believe their tongues served as an endorsement of the former President). No one believed that the Spirit is always directly behind Christian tongues speech (which I think means that all appear to believe that tongues are possible, at least sometimes, without the Spirit’s direct enablement).

A few (5%) thought demonic power might be directly involved in the misuse of tongues, and another 13% ended up in the “other” category (and I wished I left space for explanation, but alas I did not). 27% leaned towards viewing tongues as a human capacity, which has fascinating implications when it comes to using tongues as evidence for the authenticity of a Spirit baptism experience. We’ll explore more of this below, but I’ll raise the question here for those taking this view: Would this mean that some people can more easily learn this skill than others? If this is the case, this could raise further questions concerning whether tongues can be “taught,” and perhaps even whether it is unfair to exclude some from certain communal functions (e.g., church or denominational participation) simply on the basis of it being more difficult for them to “learn” this practice.

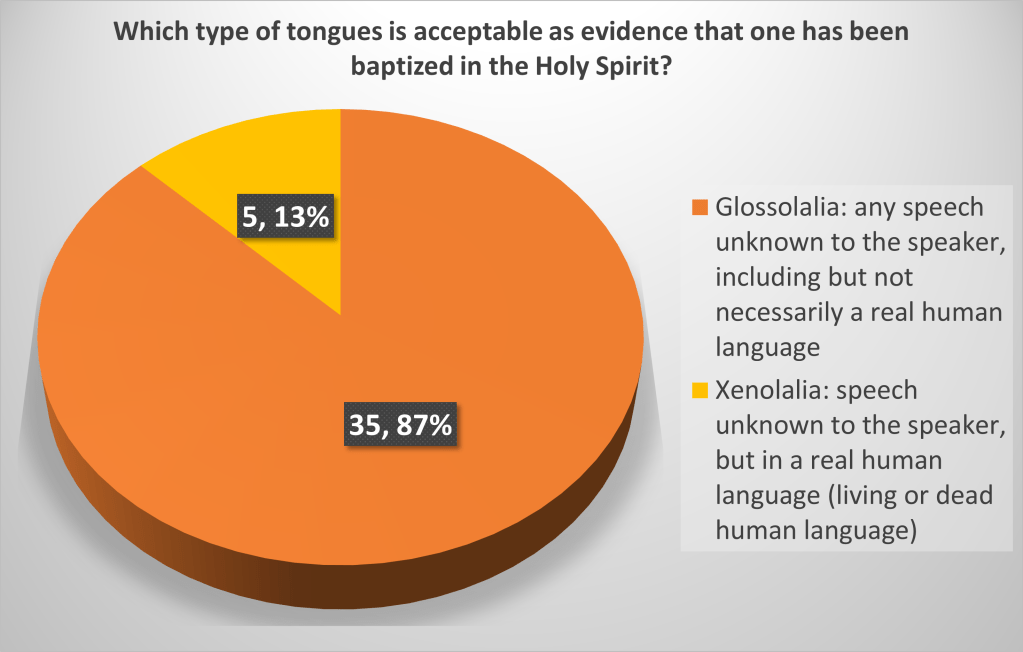

Does glossolalia or xenolalia count?

In this question I just wanted to see if any credential holders would restrict what counted for authentic tongues to anything other than glossolalia. I had thought that the response would be almost universally glossolalia, but was somewhat surprised that 13% required the more narrower xenolalic tongues speech as being required in order to identify a true experience of Spirit baptism. This also raises some fascinating questions. If Pentecostals did require xenolalia only as indicating authentic Spirit baptism, how exactly would this be assessed? Would we record the tongues and then have a panel of different language speakers listen to the tongues to determine what human language(s), if any, was being spoken?

Practical challenges aside, one strength of the xenolalia-only stance is that it might exhibit greater consistency with the experience of tongues portrayed in Acts 2, which were understood by the foreigners. In other words, on the first day of Pentecost the disciples spoke xenolalia, so why not require it today?

What type of tongues counts?

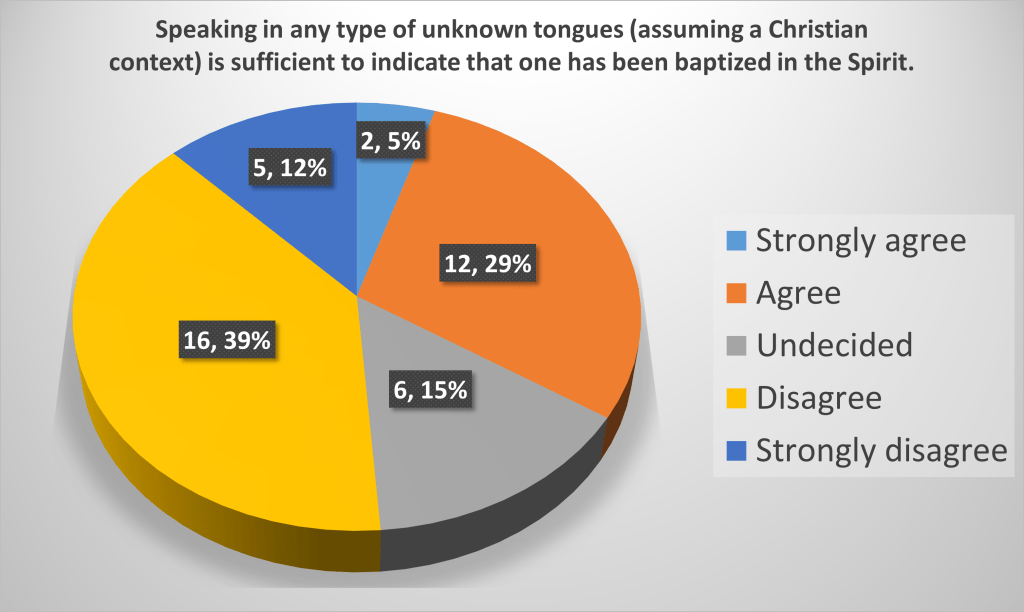

In this last question I tried to explore to what extent, if any, PAOC/NL ministers would restrict which tongues counted as evidence for Spirit baptism. We’d already seen that 87% said glossolalia was sufficient (they didn’t demand xenolalia). But what type of glossolalia? Are some forms of glossolalia more authentic than others? From the results, apparently so. (Although it could also be that I didn’t ask this question very well, but this blog isn’t going to be peer reviewed. :-))

51% of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that just any tongues could count as the Spirit baptism indicator. I initially assumed that of the five (13%) requiring xenolalia in the previous question would clearly be among the disagree and strongly disagree group for this question, and four of five were. But one respondent of these five fell among the 15% of respondents to this third question, who selected that they were undecided on the matter. 34% agreed or strongly agreed that any tongues should count as initial evidence of Spirit baptism. Qualifying this, of course, is that these are not really just any old tongues, but are tongues found at the very least in some sort of Christian context.

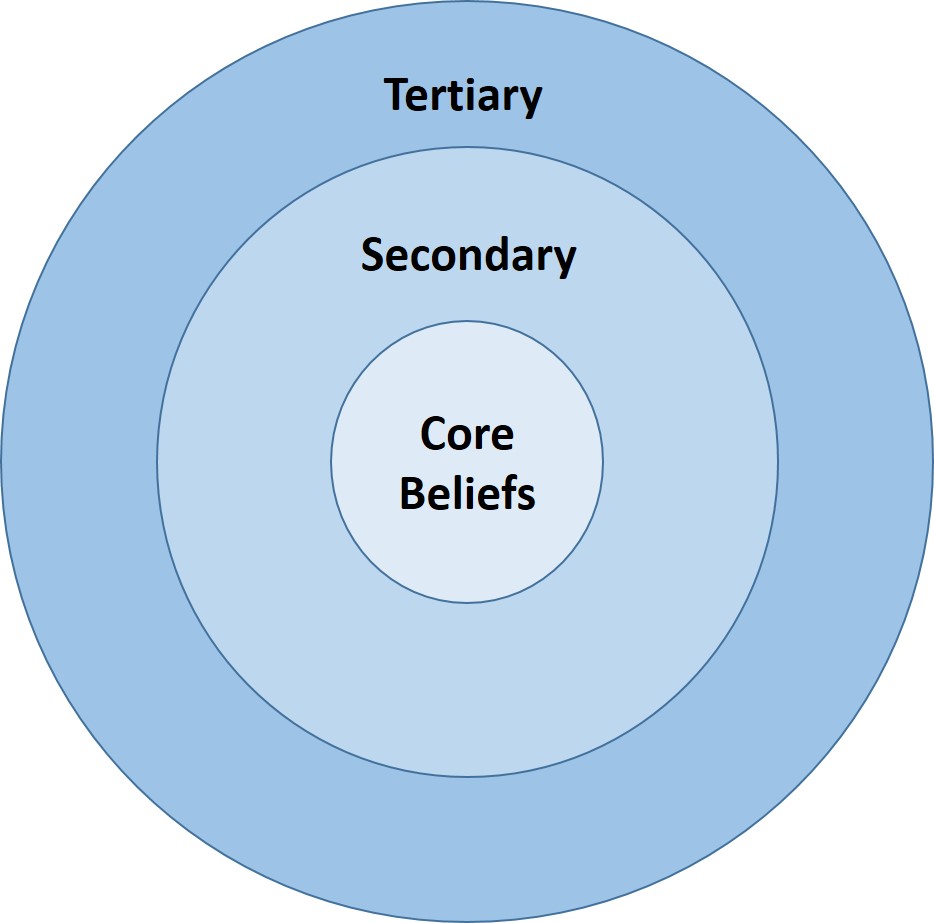

Diversity on an important matter

So, what we have here is some measure of diversity from the respondents concerning what tongues actually are (the focus of question 1), and how we can tell which tongues are authentic (the focus of questions 2 and 3). It appears, then, that there is not consensus on this matter (which tongues “count”?) at least among these Pentecostal credential holders, and this despite the reality that quite a bit is at stake socially and professionally in being able to identify whether, in fact, one has had an authentic Spirit baptism + tongues experience.

In Part 3, we’ll further explore why Pentecostals generally accept glossolalia as sufficient as the Spirit baptism indicator, but why that still doesn’t fully answer “which tongues count?”.