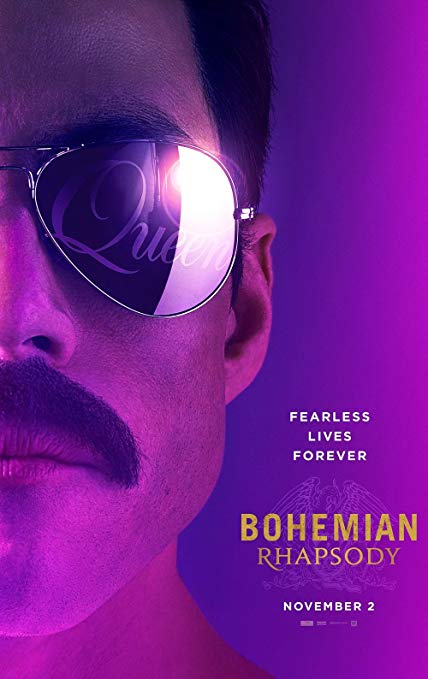

This fall I saw Bohemian Rhapsody. Three times. I never see movies three times at a theatre, let alone a biopic. So why this one?

Well, I was pleasantly surprised when I saw it the first time. I felt like I’d been to a real concert.

The backstory here is that 70s and 80s Pentecostal (and other) fundamentalist subculture passionately discouraged attending such events, and probably for some good reasons. (The farce of backward masking was not one of them.)

But having finally hit the 50-year mark earlier in the fall, my pathological need to bow to fundamentalist peer pressure was finally starting to crack. I found myself not only viewing the film, but captivated by the depiction of the rock band, Queen, and legendary front man, Freddy Mercury. I was intrigued by the creative rawness portrayed in the music-making process (at least what it was in the 70s), and enjoyed feeling something of the rapture of being caught up (no reference to dispensationalism intended) in participation with the multitude of concert-goers.

I wanted my family, especially my 21-year-old son, the guitar-player, to enjoy this experience as well. But I couldn’t get them all together for one unified viewing, and so was “forced” to go twice more (once with my wife and daughter, and once more with my son).

Everyone enjoyed the movie. We now own the soundtrack and another album or two from Queen. And I have a much fuller appreciation of Wayne’s World. Thank you, Mike Myers.

But since I’m a theology teacher, I couldn’t help but have a theological thought or two go through my mind while watching the film. In particular, I began to consider the connection between Queen and worship in the church.

Historical Accuracy: A Caveat

Before proceeding, I need to address a potential criticism of the film in order to avoid having my reflections derailed at the outset. I am aware that Bohemian Rhapsody was not entirely historically accurate on all accounts, especially timeline-wise, in its depiction of Freddy Mercury and the boys. My thoughts are only based on the movie’s rendering of the story. In other words, regardless of how historically precise the movie was or was not is irrelevant for my thoughts here. I’m simply using the film as a literary device for theological reflection. Please humour me.

In case my reference to literary device is unclear, let’s take another movie illustration. Remember in the original Spiderman film trilogy with Tobey Maguire, when uncle Ben told a young Peter Parker that “With much power comes much responsibility”? What can we learn from these wise words that’s applicable to our own lives? Much! And it’s irrelevant that there is no such historical person as Spiderman. We use a scene or dialogue from the movie or book as a tool (device) to spur on other thinking. That’s what I mean by literary device.

Now at this point my preamble has ended up being far too long, but I’m going to forge ahead anyway. I am also going to try very hard to avoid any cheesy applications here using lyrics to Queen’s songs (although in a way, didn’t Jesus come to show all of us that “crazy little thing called love”? Sorry.) Bohemian Rhapsody provoked two reflections for me concerning music and worship in contemporary evangelicalism; one is an affirmation, one is a challenge.

The Affirmation: Celebrate Creativity

Queen apparently worked hard to be creative in their music. More than one scene highlights this, but one stands out for me: the vignette of the band producing their first album.

To distinguish themselves from all the other bands out there, the band knew some new sounds were needed. Unique creativity was required, which would entail commitment and a willingness to take risks.  And so, we’re shown the young band members selling their only van to pay for time in a recording studio to produce an album. In studio, bandmembers strive to produce new sounds through experimentation—trying everything from swinging amplifiers suspended by a rope, to tossing coins on a drum. Whether Queen was the first to do this type of thing is irrelevant to me (remember, literary device!). The point is that they are portrayed as working hard, giving resources, time, and energy for the sake of creativity.

And so, we’re shown the young band members selling their only van to pay for time in a recording studio to produce an album. In studio, bandmembers strive to produce new sounds through experimentation—trying everything from swinging amplifiers suspended by a rope, to tossing coins on a drum. Whether Queen was the first to do this type of thing is irrelevant to me (remember, literary device!). The point is that they are portrayed as working hard, giving resources, time, and energy for the sake of creativity.

This reminded me of the behind-the-scenes effort musicians and worship leaders put in to helping lead congregations, week after week, in creative ways. True, it’s not quite the same context. The goal of the worship leader is not primarily (or even at all?) to stand out from all the other leaders. And yet, God has given musical and artistic gifts to the church, and creativity needs to be given room to be cultivated. Not all expressions of our creativity will make it into a Sunday morning worship context (nor should it; see my second observation below). But artistic ability—whether musical or other fine arts—needs to be respected, honoured, given room, and enjoyed in the church, since it points us to the God who is the author of creativity. Being creative takes dedication and work. It takes time and energy—actual, physical brain energy. And it takes courage to present what you’ve created, whether song, painting, dance, and so forth, to the public.

So, kudos to all of you that put in the time to use the gifts that God has given to helping us better appreciate God’s creativity. Keep it up. Maybe even try some new things. Celebrate and enjoy creativity. Bohemian Rhapsody can remind us afresh of the value of the creativity and artistry God has woven into creation.

The Challenge: Distinguish between Corporate Worship and Concert

I was also reminded of a conviction I’ve held for some time, which is that a distinction needs to be made between a music concert and congregational singing in worship. I realize there is disagreement on this, depending on one’s philosophy of worship. See James MacKnight’s excellent recent blog on this here. And trust me, the title of his blog is cleverly and intentionally misleading—please read it!

My view is that worship serves a purpose, which is related to elevating the human view of God and forming people to reflect God’s image more accurately in and through relationship to Christ. In short, worship needs to be connected to the formation of disciples of Jesus, which in turn glorifies God. For me that is a central criterion for determining whether corporate worship is, well, worship at all. This means I tend to think there needs to be a mostly clear distinction between the concert venue and corporate worship venue (with some blurring of categories being inevitable). More about this in a moment.

In another scene in Bohemian Rhapsody, lead guitarist Brian May has band members join him on a studio riser and begin stomping their feet and clapping with their hands to the now famous beat of “We Will Rock You.” May explains that he wants the fans to be able to participate more in Queen’s concerts, since they’ve already been trying to sing along with some of the band’s songs. What instruments does the average concert-goer have? Feet and hands. The audience is intentionally being invited to be part of the band, part of the musical experience.

The fact that participation is being made intentional here is noteworthy, since the crowd has gathered not to hear one another’s voices, but to hear Freddy and the band. Yet the recognition of what spectator participation does to enhance the overall concert experience leads Queen to purposefully incorporate crowd involvement into their act. Both band and audience participate in something bigger than what either could produce on their own.

Concert or Corporate Worship?

Back to corporate church worship. Above I proposed that corporate worship is not to be confused with a Christian concert. I’m not opposed to concerts, Christian or otherwise. They can be enjoyable, encouraging for faith, and simply fun. Why not? But concerts are not corporate worship, which exists for another purpose.

One criterion, for example, that I believe corporate worship needs to fulfil is to make the congregation appreciate that they are communally the body of Christ, the people of God. They must not only know this rationally (e.g., from points in a sermon), but must learn to feel this deeply and (eventually) intuitively. This can be encouraged in a number of ways, but our focus here is only the corporate worship context. In this setting the formation of the sense of communal belonging happens by actual participation in worship together, corporately.

Worship structure, including music, that does not encourage this bonding (what the NT calls “fellowship”—a shared value of spiritual commitment) may actually work against forming participants into thinking and feeling themselves to be members of God’s unique people. In other words, if the structure encourages the regular practice of being an observer, rather than a contributor to the worship experience, then the worshipper will learn intuitively that Christians are individual observers. And perhaps even that worship is about “me and Jesus” and not all those other people who happen to be around me. (By the way, isn’t this exactly what we are inclined to learn when we turn down the lights in worship, so we won’t be distracted by those around us?)

In other words, it’s quite likely that confusing a concert model with corporate worship actually works against at least some of the goals of corporate worship. Rather than offering an alternative to the powerful social forces and rhythms of secular culture—which shape and form us to be, above all, autonomous individuals—the concert model in many ways simply reinforces these.

(Sidebar: To support the above paragraph, and outlining the power of habitual action for discipleship formation, I would highly recommend James K.A. Smith’s, You Are What You Love. He outlines a rationality for discipleship formation by arguing that we become like what we love, what we desire most deeply. Regular, repetitive individual and corporate behaviours have the most impact on shaping what we love.)

Remember the Audience

Where am I going with this? I believe that much current corporate worship is modeled on a concert framework and attempts to evaluate itself based on concert criteria: excellent musician performance and crowd enjoyment (with maybe some participation). I believe this approach to be misguided and in the long-term simply reinforcing of cultural values that we perhaps later try to unsuccessfully mitigate with points in a sermon. I don’t want to overstate this point, since God works powerfully through worship teams despite using the concert model, but I’m convinced it’s not the best practice for discipleship formation.

What is best (or at least much better) practice is for the musicians to bear in mind that the corporate worship context is for the purpose of corporate worship. It is intended to encourage as much crowd participation as reasonably possible in our sometimes very large gatherings. Yes, the worship leaders are still called to excellence, but excellence is evaluated not on performance or every aspect of musical ability being expressed, but in large part on how well the congregation was able to participate in giving honour to God with mind and body (and without having had to practice their singing in advance).

If the average congregation attendee can only with great difficulty sing the songs being used on a Sunday gathering, we just might want to consider whether this really encourages participation or not. If it hinders participation, then something needs to change; that is unless something we value more than corporate worship as discipleship formation is driving us.

In any case, Bohemian Rhapsody brought afresh to my mind the need to remember the audience. In fact in one more memorable scene (my son calls it magical) the band is performing in Rio. The Portuguese-speaking audience spontaneously beings singing the English words to “Love of My Life.” Now, please ignore the fact that the film presents this concert probably a full ten years before it actually happened. (Remember, literary device! And to watch this magical moment from Rio in 1985, see here.) My point is that in the movie Freddy Mercury serves as an excellent example of one leading a crowd to sing a song together. He hardly even sings much of the song, even using his hands and arms to guide the crowd, since he knows he is no longer performing but leading. If Freddy could recognize a difference between performance and participation in his concerts, then maybe there’s something to this distinction after all.

Creativity Serves Worship

One more thought. Perhaps we can put both these ideas together: celebrating and encouraging creativity for the purpose of corporate worship. Creativity in this case will entail hard work and sacrifice, but will more intentionally be directed to an end—corporate discipleship formation. Here creativity does not exist for its own sake, but deliberately serves a bigger purpose. It may even recognize that constant innovation in corporate worship is arguably not best practice for long-term discipleship formation; creativity needs to serve a larger framework.

One application that I would encourage is that those creatively gifted in composing music and lyric-writing aim especially to write pieces that are not only biblically faithful (notice I didn’t say theologically complex), but also that are easy to sing corporately for the average person. Create songs that encourage maximum participation, with the goal building up one another into Christ’s body (Eph 4).

Who knew that Freddy Mercury could teach us so much about leading worship?