Now we come to the final tip in this series. To recap, during times of doctrinal change and uncertainty our inner and social worlds may feel considerably destabilized. This uncertainty is due to the multifarious opinions on pretty much all theological matters online, in books, podcasts, webinars, and so forth. And even more personally, for me, this uncertainty is intensified because my denomination, the PAOC, is undergoing a “doctrinal refresh,” and rewriting its doctrinal articulation, its Statement of Fundamental and Essential Truths (SOFET).

The full SOFET revision in scheduled come to the General Conference floor for some sort of decision in 2020. So, approaching this event, I thought it might be helpful to process not the specific content of PAOC doctrinal beliefs, but instead how we process our beliefs in general. Understanding this will provide a framework for decision-making when it comes to doctrinal decision-making. Let me also state here that the points in this blog series are not intended to be applied only to PAOC contexts. I’m really trying to outline a helpful way for Christians of all stripes to think about their beliefs.

To this point I’ve recommended two tips in my previous blogs in this series: 1) Don’t panic (dealing with the psychological impact of challenges to our beliefs), and 2) Be humble when it comes to what we think we can know, and be ok with some level of uncertainty.

Now we come to the final tip.

Tip 3: Accept that there are Levels of Theological Truth (not all “fundamental and essential truths” are necessarily fundamental or essential for Christian faith)

Off the bat this might look like I’m challenging the title of the PAOC’s SOFET, but that’s not really my goal here (I can live with the title). The challenge is that the SOFET contains doctrines that are neither fundamental nor essential to Christian faith. This doesn’t mean these are not important doctrines (especially if one intends to hold credentials with the PAOC); it simply means that one can be a faithful Christian without believing every single one of these doctrines. Some of the doctrines are more fundamental and essential than others.

The point is this: There are levels of theological truth, and we need to accept this to function well not only in times of doctrinal refreshes and disputes, but throughout life in general, if we hope to grow in maturity in Christian faith and to avoid psychologically injuring ourselves personally and corporately by living in a state of over-protective hyper-vigilance.

Lest this seem to be my opinion alone, I’m happy that this very point was made publicly by a member of the SOFET committee during a presentation at the PAOC General Conference earlier this year (May 2018). One goal of the SOFET refresh in part is to help better focus the content on what is really fundamental and essential, giving less emphasis to what might be less central. There was no dispute raised on the floor to this idea, and so I will take this silence as tacit consent to the general point I’m making here 😊.

To appreciate this, we need to better understand how we tend to hold beliefs mentally.

A Common Belief Model: The House of Cards

One of the most helpful illustrations regarding how we tend to hold beliefs comes from Gregory Boyd’s, The Benefit of the Doubt. He proposes two models for how we hold our beliefs psychologically: a house of cards and concentric circles.

The house of cards model refers to the pastime of building a “house” using playing cards by leaning one card up against another. By progressively adding cards, an impressive structure can be erected. Provided that all the cards remain in place, one can continue to add to the structure, making it ever more complex. But the very method of construction is also the inherent weakness of this house. Every card relies on all the others for its stability. Remove one card and the entire house collapses.

Boyd says that often Christians hold their beliefs in a similar way. This is often due to what I addressed in my second tip (part 3 of this blog series), that we may have learned to take all teaching we have received from pastors and Christian leaders as absolute truth. All of it. And when we do this, we begin to feel that each of these “truths” bears equal importance. No one likely asserts this explicitly, but it becomes a psychological reality. Each “truth” functions like a card in the overall doctrinal house of cards. Each conviction is so emotionally connected to the others that each comes to bear almost equal weight. We feel it deeply because we’ve learned to do so. And when all the beliefs are in place, we feel safe within the walls of our cozy card-house fortress.

This does imply, however, that each card in our fortress needs to be protected as if our life of faith depended on it. For if even one belief is doubted, or turns out to be untrue, the entire mental structure is jeopardized, and this can easily lead to a crisis of faith.

For example, we might happen to discover, despite what our pastor perhaps strongly preached, that the evidence for a pre-tribulation rapture in Scripture is not so blatantly obvious as we supposed in contrast to other timing-of-the-rapture theories (or even more unsettling, that there might be far less scriptural evidence for a two-stage return of Jesus than assumed in dispensationalist systems!). Now, please know that this paragraph is not intended to open the door for a debate on eschatology and Left Behind novels—that’s not the point. The example above is only intended here for hypothetical illustration. The point is that if one becomes less sure about something they were told was very true, and they find out it isn’t necessarily as true (or maybe outright false), and if that doctrine was promoted as being of great importance (such that to not believe it would make your commitment to Jesus or at least the church community suspect), then this does open to door to wondering what else you were taught that doesn’t have quite the scriptural backing you thought. And this, I believe, is the place many faithful Christians are in today.

In the house of cards model, once one conviction is weakened the entire structure is threatened. When one doctrine is removed, the edifice collapses.

How the House of Cards Model Affects Us

How does this affect those holding this model, practically? I will stereotype here for convenience, but this I think the following is fairly accurate.

Personally, holding this model has the advantage of providing a feeling of assurance and confidence; at least most of the time. And this feeling feels so good. However, it also comes with potential anxiety over losing this feeling by being exposed to new information or ideas that do not fit within the card house, and so one needs to be vigilant to spot any maverick theology that might threaten the safety of the card fort. Theology in this view is often assumed to be a fixed discipline; theology is something figured out by theologians about 500 years ago or so (in Protestant traditions and their offspring). Currently, all we need to do is package theology in new ways to ensure cultural relevance. The content doesn’t (should not!) change, and so all that’s required is be reminded from time to time of what we believe (i.e., what has been resolved once and for all), and then market this content better (or not). But any revisions to theology are considered threatening in this model because they are considered a movement away from a static deposit of truth. So, personally opening oneself to, say, new scientific discoveries, or alternative Christian viewpoints on any number of matters is by default a move away from truth and toward a potential collapse of faith. Openness to knowledge from outside the doctrinal system is often considered too risky, and so one avoids listening to other than what one has been taught.

Socially, this model does connect people in strong ways, provided they all agree on pretty much everything. But this requires a hyper-vigilance among those in the particular church community. One must not only constantly evaluate oneself, but also others to determine whether they are in or out of, or poses a danger to, the house of cards. Public expression of doubts, questions, or alternative ideas is discouraged on threat social exclusion (or at least not being quite “trusted,” which removes leadership opportunities). Theologically, this model can encourage debates concerning non-essential theological matters, since there are (almost) no non-essential theological matters! Such communities are ripe breeding grounds for judgmentalism and theological witch-hunting.

Although there are positives—feeling certain and being strongly connected to like-minded others—the house of cards model is not sufficiently flexible for mature Christian faith. The world is more complex than this model allows, and it fails to acknowledge that humans can continue to grow in knowledge of God and the universe. Another model is needed.

A Better Belief Model: Boyd’s Concentric Circles

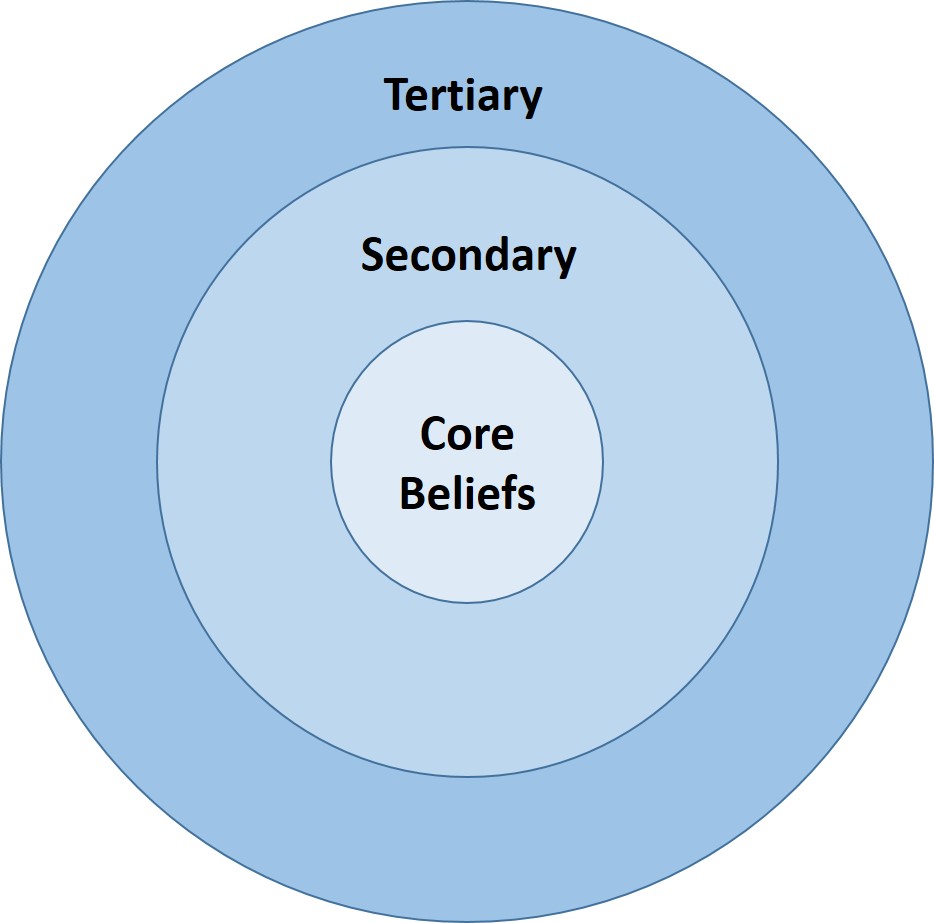

As an alternative to the house of cards, Boyd recommends a concentric circles model of beliefs. In a concentric circle, certain beliefs are more central or core than others. Outside the core are beliefs that are of secondary or tertiary importance. This does not mean that beliefs outside the core are not significant; it only means recognizing that not all beliefs are as vital as others. In this model beliefs are still connected to one another, but we ought to hold more tightly to those in the core, and less tightly to those further from the centre.

Is this idea itself biblical? I think so. For example, 1 Corinthians 15:1-3a sates,

Now, brothers and sisters, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand. 2 By this gospel you are saved, if you hold firmly to the word I preached to you. Otherwise, you have believed in vain. 3 For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance… (NIV)

The Apostle Paul goes on to describe “the gospel,” which serves as the ground of faith upon which Christians stand. Paul believed that some beliefs are foundational to the Christian faith, and this implies that others are not. Foundational beliefs are, then, those we can consider within the core of the concentric circle model. Not all beliefs can fit into the core, since not all serve as the ground of Christian faith.

Again, this doesn’t mean that other beliefs are not important, but not all are essential or primary in this way. It does mean, however, that we need to consciously commit ourselves to the idea that some convictions are second- or third-level convictions (or beyond). While valuable, non-core beliefs deserve to be held less tightly than others, and we need to be more cautious about allowing these to serve as criteria for Christian fellowship. A partial exception to this might be when it comes to denominational or church membership, but when it comes to accepting someone as a fellow Christian, the core beliefs are what ought to provide the criteria, and not those outside the core.

How the Concentric Circles Model Affects Us

Practically, what’s the benefit of the concentric circles model?

Personally, it helps us be less anxious when we feel less than certain about one of our beliefs, especially the non-core ones. We can incorporate questions and doubts into the overall process of maturing in our life of faith. We’ll be able to experience correction and modification of our beliefs, and ideally be open to pursuing truth wherever it might be found in God’s creation.

Socially, this model makes it easier to make room for others with different opinions. They will no longer be viewed as spiritually inferior or as a threat to the faith fortress. Instead, there will be an appreciation of diversity within Christ’s body in both beliefs and practices. And this should overall contribute to a healthier, stronger missional environment, since we will be less concerned with defending the fort, and more concerned with outreach.

The Spider’s Web: Supplementing the Concentric Circles

Now, it’s one thing to rationally adopt the concentric circles beliefs model, but quite another to live it.

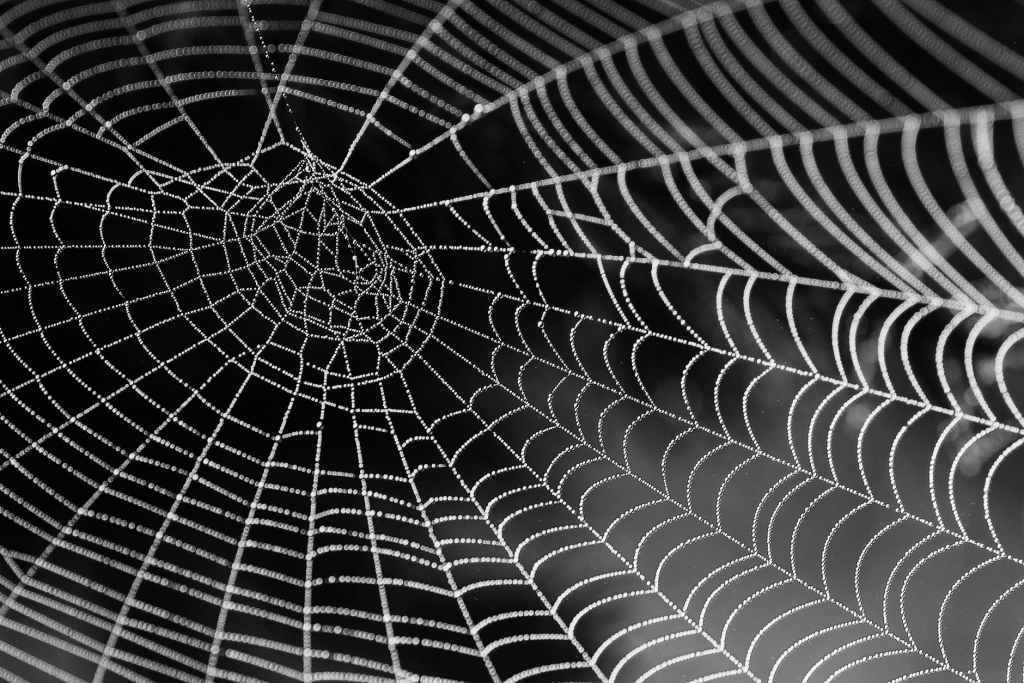

John Stackhouse supplements our discussion here by likening the way we hold our beliefs to a spider’s web (I think it was here that I heard him mention this). Any touch on one strand of the spider’s web reverberates through all the others, signalling the spider that it may be lunchtime or that an enemy is near. For us (non-spiders), when a question, doubt, or unfamiliar idea begins to tug at a strand even at the peripherals of our belief web, it vibrates to the core of our psychological and spiritual being. Even if we have rationally determined that a particular doctrinal belief we hold is non-core (say, whether biological evolution is involved in God’s creation process or not), when a challenge to that belief is presented, it may very well feel like our core beliefs are being compromised.

The spider’s web analogy should encourage patience with ourselves and others as we move from a house of cards model to a concentric circle model. We may rationally decide the latter model is the better option, but it will take our brains a while to catch up emotionally. It will be a slow learning process, so be ok with that. I think God is patient with us in the process too.

What’s in the Core?

All of this, of course, raises the question of what exactly should fit into the core of our Christian beliefs. And this is probably another area where Christians will disagree! But I don’t think we are left without wisdom in this regard.

Boyd proposes that any belief that is not directly necessary for linking one into relationship with Jesus should be considered peripheral to the core. This is good and helpful, but I’d like to propose another way of identifying what’s core. For me, what belongs to the core of Christian beliefs are those without which there would be no faith to talk about.

What would those beliefs be? I think that those outlined in 1 Cor. 15 are a good start (you can find this chapter here). There Paul states that the gospel, on which believers take their stand, is the story of God’s work in and through Jesus, through whom all things will be made right. This includes, then, the following beliefs:

- The triune God exists and is working salvifically in the world he created

- The Bible occupies a privileged role through which God reveals his salvation plan through Jesus

- Jesus is the incarnate God-man who lived, was crucified and resurrected

- Jesus ascended and poured out the Spirit at Pentecost shaping church life

- Jesus will return and reconcile all things to the Father forever

A similar content is found in the Apostles’ Creed. That’s what’s core to the Christian faith, since without it, there is no Christian faith to talk about. This is not a story primarily about me or us, but the story of Father, Son, and Spirit, who wants to include us in the divine story.

What would fall outside the core? A whole lot. In my view this would include matters such as how God created the universe and humans and when, whether Jesus returns in two stages or one, whether God meticulously governs the universe or allows a measure of libertarian freedom to humans and other spiritual agents, whether tithing is necessary or just a helpful spiritual practice, and so forth. Such would not be core to Christian faith, but again this does not mean that these are not important—I tend to think some of these issues are very significant for how we live out Christian life. So some of the above would be closer to the core for me, but not in the core. This also doesn’t mean that opinions on these issues are all of equal value. Some may have more biblical and theological support, and so be truer than others. It’s just that they are not core to Christian faith.

Finally, it also needs to be acknowledged that whether a non-core doctrine is still retained as a denominational credential or church membership requirement is a different matter. Denominations need to be practically allowed space to define who will be allowed in their leadership or membership, and so even secondary and tertiary beliefs may be identified as “essential,” not for being a Christian, but for holding association within a formal institution. My only caution in this regard is that denominations should probably add as few non-core doctrines as possible to their membership essentials (just like the church did in Acts 15). This will help the denomination avoid ghettoizing itself, and open it to the potential creativity and ideas of those who may have different views, backgrounds, and experiences than those traditionally embedded in the formal organization. As a Pentecostal, I happen to think that Acts 2 and 15 encourages holding less tightly to non-core matters of doctrine and community ethics for the sake of mission, and including all sorts of others so we can better bear witness to Jesus. But that’s all I’ll say about that here.

My hope for this four-part series has been that it would provide a way of navigating through doctrinal uncertainty and change. If it has helped you or if you have further questions or thoughts, please let me know by commenting below (or by sending an email). Thanks for reading!

Reflection

- Have you been holding your beliefs in more of a house of cards or concentric circles model? How has this psychologically affected the way you’ve lived out your faith?

- What theological truths would you place in the core, and which ones would you place outside of the core? Why? What non-core beliefs are closer to the centre for you, and why? How do you determine what belongs in the core?

Peter Neumann is available to speak at your church or other gathering about this and other theological and topics, including: emerging adults and faith, salvation, the Holy Spirit and Pentecostalism, and other questions about the Christian faith. Peter can be contacted at peter.neumann@mcs.edu.

Gregory Boyd’s,

Gregory Boyd’s,  creatures made in God’s image, and have accomplished much. But we are not God. Only God has all knowledge (omniscience), and I’ll leave it to the Calvinists and Open Theists to argue about how to define that knowledge 😊.

creatures made in God’s image, and have accomplished much. But we are not God. Only God has all knowledge (omniscience), and I’ll leave it to the Calvinists and Open Theists to argue about how to define that knowledge 😊. At the same time, while humans cannot know everything, we can learn and know lots of things. In fact God has called us to learn about himself and creation, and to continue to do so with the resources he’s provided (the Bible being the privileged resource in a dialogue that involves the voices of Christian tradition, arts, sciences, and experience). With God’s revelation and our cognitive abilities, he calls us to learning about himself, ourselves, and creation as part of what it means to bear his image. This means that theology is not a static deposit of propositions about God, but is a dynamic and growing endeavour. It may very well be the case that failure to learn and grow in knowledge—about God and the world—may even be a matter of disobedience to God’s call on humans beings to bear his image in this world (see

At the same time, while humans cannot know everything, we can learn and know lots of things. In fact God has called us to learn about himself and creation, and to continue to do so with the resources he’s provided (the Bible being the privileged resource in a dialogue that involves the voices of Christian tradition, arts, sciences, and experience). With God’s revelation and our cognitive abilities, he calls us to learning about himself, ourselves, and creation as part of what it means to bear his image. This means that theology is not a static deposit of propositions about God, but is a dynamic and growing endeavour. It may very well be the case that failure to learn and grow in knowledge—about God and the world—may even be a matter of disobedience to God’s call on humans beings to bear his image in this world (see  But again, the feeling or attitude of certainty is not necessarily connected to whether our beliefs are true or not. I can feel absolutely certain about something, and be absolutely wrong. And in case you think I’m sounding too relativistic or “progressive” here (sometimes used as a default blanket term to dismiss anything not traditionally American evangelical), William Lane Craig argues the same thing in a recent podcast (

But again, the feeling or attitude of certainty is not necessarily connected to whether our beliefs are true or not. I can feel absolutely certain about something, and be absolutely wrong. And in case you think I’m sounding too relativistic or “progressive” here (sometimes used as a default blanket term to dismiss anything not traditionally American evangelical), William Lane Craig argues the same thing in a recent podcast ( all times. Our levels of certainty about our beliefs will ebb and flow depending on mood and circumstances. At times Christians will feel unshakable confidence about particular doctrines of the Christian faith. Singing our favourite song about God’s love while in an inspiring celebration service may evoke deep assurance that we are indeed loved by God. But the next day, when faced with difficult challenges, our feeling of certainty is not quite as strong. Have we lost our faith? No. What we’re experiencing is the ebb and flow of our emotional state. What we should do is grow in our trust in God and accept that the diminishing feelings of certainty are not the foundation of our relationship to God. Demanding certainty as a virtue will ultimately lead to failure to live up to this ideal, and lead to discouragement, and possibly unnecessary guilt and shame.

all times. Our levels of certainty about our beliefs will ebb and flow depending on mood and circumstances. At times Christians will feel unshakable confidence about particular doctrines of the Christian faith. Singing our favourite song about God’s love while in an inspiring celebration service may evoke deep assurance that we are indeed loved by God. But the next day, when faced with difficult challenges, our feeling of certainty is not quite as strong. Have we lost our faith? No. What we’re experiencing is the ebb and flow of our emotional state. What we should do is grow in our trust in God and accept that the diminishing feelings of certainty are not the foundation of our relationship to God. Demanding certainty as a virtue will ultimately lead to failure to live up to this ideal, and lead to discouragement, and possibly unnecessary guilt and shame. perhaps more so than it is to truth. Some people are simply very confident in their opinions; they feel and display certainty concerning—just about everything! Sometimes that is what preachers believe they must portray in public. But I think we need to be careful about making this a model, especially since it will immediately alienate those whose personalities don’t share this ubiquitous confidence.

perhaps more so than it is to truth. Some people are simply very confident in their opinions; they feel and display certainty concerning—just about everything! Sometimes that is what preachers believe they must portray in public. But I think we need to be careful about making this a model, especially since it will immediately alienate those whose personalities don’t share this ubiquitous confidence. while being open to revision, should God choose to correct our understanding (through Scripture, a direct message from the Spirit, or even through study of science and history).

while being open to revision, should God choose to correct our understanding (through Scripture, a direct message from the Spirit, or even through study of science and history).

This doesn’t mean we can’t hold convictions or stand up for truth. But we are not required to avoid uncertainty (nor are we able to).

This doesn’t mean we can’t hold convictions or stand up for truth. But we are not required to avoid uncertainty (nor are we able to).