If you’ve spent any time in a typical evangelical or Pentecostal church, you’ve likely heard that Christians are called to give a “tithe” of their income to the church, but one may also give over and above, voluntarily, an “offering.” The tithe is expected; the offering is a freewill gesture. But is this involuntary/voluntary distinction between the tithe and offering supportable biblically, or is it more a distinction resulting from tradition or pragmatism (i.e., it’s a convenient and helpful practice)?

(If you read to the end you can give your feedback in a brief poll, so read on!)

I’ve just finished reading, You Mean I Don’t Have to Tithe?: A Deconstruction of Tithing and a Reconstruction of Post-Tithe Giving, by David A. Croteau (a book in the McMaster Divinity College’s Theological Studies series). For one raised in a tradition that assumed tithing to be an established biblical principle, applicable from the time before Moses to the current day, I’ve found this carefully researched study to be both challenging and refreshing. Related to the above question, Croteau is helping me rethink the tithe/offering distinction.

Tithing Then

For context, many Christian today understand tithing as the practice of giving one tenth of one’s income to one’s local church. This practice is usually grounded in certain Old Testament Bible passages that mention God’s people, both before and during the implementation of the Mosaic law, as giving a tithe of their resources indirectly to God. I say indirectly because actually the resources were given to people whom God had designated to be recipients of the tithe.

For example, the Levites were a tribe of ancient Israelites who were called to dedicate themselves to religious service. But this meant that unlike other tribes they had not inherited any land (aside from four dozen cities) on which to grow their own food. Non-Levite tribes were to tithe of their resources (specifically, the produce of the land, with other forms of income not being mentioned) so that the Levites might have food, and be able to dedicate themselves explicitly to sacred ministry. It was God’s way of ensuring that the Levites shared an inheritance along with the other tribes.

Aside from tithing 10% to the Levites, ancient Israelites were required to participate in other regular tithes, which, according to Croteau, totaled about 20% of their resources (others report a bit less or a lot more, but 20% seems a reasonable number here). So where did the idea of only a 10% tithe come from?

The 10% cap is often tied to pre-Moses Israelite history. Here Abraham serves as the prime example, having given 10% of his spoils of war to the enigmatic priest, Melchizedek. Croteau does note that Abraham’s tithe is only ever mentioned as a one-time event and not a regular practice, but leaving that aside, the point here is that the 10% number used here has become a firmly established biblical directive for Christian giving today. But how exactly did that happen, and how did the sharing of agricultural resources expand to include other gross income?

Tithing Now

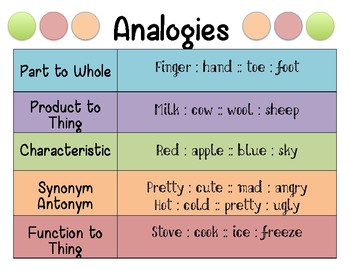

The popular application for tithing today, as far as I understand it, reasons by analogy more or less along the following lines.

- Just as ancient Israelites tithed to a group overseeing sacred work (Levites), so too must Christians today tithe to support sacred and Christian missional work.

- Nowadays, since pastors and/or church staff function in ways roughly analogous to Levites, tithes should go to the church to support the pastors/staff and the general work of the church.

- Further, since we don’t function primarily as an agricultural society, we don’t give the fruit of the land, but a percentage of our earned income (and I will skirt the gross vs. net debate here).

The tithe, again, is considered a requirement for all Christians, often regardless of one’s financial situation. To not tithe is often deemed as stealing from God, based on a very literal application of an OT text, Malachi 3:8 (which we will return to shortly). So, in this logic, tithing is important and negligence of this duty is no small matter.

Interlude: Giving Is Good

Let me interrupt briefly and say at this point that I’m all in favour of supporting pastors, teachers, and church ministries with ample giving. Generous giving is needed to help the church (and parachurch ministries) do what they’re called to do. Very often those called to such ministries are personally sacrificing much to be faithful to their God-given callings, and the corporate church needs to share in supporting the ministries they believe should be operating, including caring financially for those who have given up other opportunities to serve in this capacity. The New Testament (NT) clearly calls Christians to do this. So, this post should not in any way be viewed as questioning the necessity of sacrificial giving of all Christians to support the local church and other charitable ministries.

In fact, while Croteau does propose that we ditch all tithing language for Christians today and recognize that we live in a post-tithe era, he nevertheless argues that generous and sacrificial giving is a crucial practice for followers of Jesus. In the place of tithing he argues that the NT provides very good directives that, if accepted, should lead to greater generosity among Christians. He anticipates that following NT giving principles, rather than tithing, would lead many believers to start giving more than an obligatory 10%.

My purpose here, however, is not to explore those NT directives, and so I recommend that you read his book and see what you think.

And now back to the point.

What’s the Deal with “Offerings”?

As noted, a favourite go-to passage in support of present-day tithing is Malachi 3:8-10:

“Will a mere mortal rob God? Yet you rob me. “But you ask, ‘How are we robbing you?’ “In tithes and offerings. You are under a curse—your whole nation—because you are robbing me. Bring the whole tithe into the storehouse, that there may be food in my house. Test me in this,” says the Lord Almighty, “and see if I will not throw open the floodgates of heaven and pour out so much blessing that there will not be room enough to store it.

Malachi 3:8-10 NIV

Croteau thinks that Malachi 3 is simply been misused when directly applied to Christian programmatic giving today. But again you’ll need to read his book to explore the reasons why. Here I just want to focus our attention on the two key words at the end of v. 8 — “tithes” and “offerings.”

We’ve already surveyed how the concept of tithe is often applied today. But what about “offerings”? After all, both tithes and offerings appear in this very same passage, and so if one is deemed applicable for today, to be consistent, so too should the other. And indeed what I’ve heard pretty much my entire life is that both of these terms can be applied to Christians giving today, but with an important distinction. One type of giving is assumed obligatory and the other not.

To recap, tithing (10% of one’s income) is obligatory for the Christian. That is the minimum expected. But one doesn’t have to stop at 10%, and may also give more, although one is not required to do so. Anything given over and above the tithe, then, is given voluntarily (freely), and is labelled an “offering.” In short, how this is generally conveyed in many churches today is that the tithe is expected of every Christian believer, but offerings are a freewill gift that Christians may give over and above the tithe minimum. Some churches may even teach that tithes are for general church operations, but offerings are over and above, and may be applied to such things as giving to missionaries, building programs, special outreach events, etc.

In any case, these two types of giving — obligatory and freewill — find their biblical basis and defined distinction in Malachi 3.

Or do they?

No Freewill Offerings?

Croteau gives us reason to be less certain of this involuntary/voluntary giving distinction (and oh how we hate uncertainty!). He notes that the offerings in Malachi 3:8 would have been understood in that context not to be freewill gifts over and above the tithe, but instead as a different category of obligatory giving. Offerings, he explains, were particular donations designated to support the priests in their temple duties, in the form of sacrificial foods (e.g., meats and bread cakes). This category of donation is exemplified in what are known as peace offerings, wave offerings, and so forth (Ex. 29; Lev. 7). But contrary to being optional, says Croteau, “Like tithes, these were compulsory contributions required by the Mosaic law for the temple staff.”

…the offerings in Malachi 3:8 would have been understood in that context not to be freewill gifts over and above the tithe, but instead as a different category of obligatory giving.

So, “offerings” were not freewill in contrast to obligatory tithes. Rather, both tithes and offerings were required of Israelites. There was not, at least in the Malachi passage, any idea of a distinction between involuntary and voluntary giving. Again, it was all obligatory.

And aside from Croteau’s historical-cultural observation, it seems to me that this makes better logical sense of the passage as well. One can hardly be accused of robbing God by witholding freewill offerings that one was never obligated to give in the first place, right?

So, the common idea that tithes and offerings are categorically different based on distinct motivations (involuntary/voluntary) cannot be supported by Malachi 3:8. We might look elsewhere in Scripture to support giving over and above what was expected in ancient Israel, but not to Malachi.

Well, so what if both these and offerings are obligatory in Malachi? Glad you asked.

Options for Offerings

If tithes are required today, based on Malachi (and other texts), then why not offerings too? But then we must ask, what exactly would be analogous to an offering today? Remember, an offering is not simply a freewill gift. It is obligatory as much as the tithe. So, if the tithe is 10%, then what ought we to require with regard to the offering?

We have several options. Here are three main directions I think we could take.

1) We could continue to assert that “offering” means a freewill gift, over and above what’s required in tithes. But if Croteau is correct (and if the logic of the passage is to remain coherent), we would have little textual support in Malachi for doing so. We could stop using Malachi for this distinction, however, and maybe that would solve the problem. Although that might also mean coming up with another term other than “offerings” for this type of freewill gift, since Malachi is the one who provides the term.

2) We could, alternatively, stick with Malachi and introduce an “offering” requirement in churches on top of the tithe. This would entail deciding on a fixed amount or percentage that seemed reasonable for the obligatory offerings. So, every believer would be expected to give a 10% tithe and X% in offerings. But that idea might not gain traction quickly, and I’d prefer not to be the one to introduce it!

3) Another option is to simply say that, in contrast to the tithe, the offering in Malachi is no longer obligatory — it was a required sacrifice then, but this requirement no longer applies today. But there’s a consistency problem here. On what grounds would we say obligatory offerings do not continue, when we use the same Malachi passage to largely ground the continuation of tithing?

Which of the above three options do you think would be the most supportable and helpful? How would you overcome the difficulties in selecting that option? Or, what other options might be a way of solving the case of Malachi’s missing “freewill” offering?

A Poll!

There are two ways to respond here. One is to leave a comment. The other is to respond to the quick poll below so we can find out what you’re thinking about this topic. Please take a few seconds to respond to the poll. Thanks!