(For part 2 of this series click here.)

Finding Ananias and Sapphira today

Does this type of sinful activity happen today within local church communities and denominations? Do people, even leaders, ever try to use force, status (position of privilege), or money to leverage the broader church community for self-serving ends, to gain more privilege(s)?

We would hope not, but if we’re honest, unfortunately, I think we need to admit this still happens. In such cases force isn’t as frequently utilized, since it’s less socially acceptable; but status and money don’t always raise as many red flags for us, allowing this duplicity and testing of God to still occur in ways analogous to the actions of A&S.

What might this look like today? I think we see parallels of A&S today whenever people use their status, heritage, or position to intentionally ensure that their voice is the privileged one in the room. It happens even in more crass forms similar to A&S, when an apparent benefactor promises a generous donation only if, or threatens to withhold a promised contribution unless, the benefactor receives what they desire.

When venomous leveraging is allowed to operate within the church, the community becomes poisoned, and its cohesion begins to break down, including its ability to bear true witness to the new righteous and truthful kingdom of Jesus. In short, unchecked manipulation within the community threatens gospel proclamation. That’s why Peter says that such “benefactors” may very well find themselves being used by Satan.

While people echoing A&S’s manipulative behaviour today don’t usually drop down dead, Satan still tries to influence the church in this way, and God still despises this type of action. We don’t need to wait for an act of God; Acts 5 provides the church with the object lesson.

How should the church respond?

What should we do if we suspect this type of behaviour is operating in our midst? Here we need to move slowly and carefully, since situations are often complex and not always easy to judge. Each case needs to be carefully examined on its own merit to avoid making errors of association with other cases that seem (but may not be) quite the same. We certainly need the Spirit’s help to discern any given circumstance.

The need for discernment

Perhaps the offending individual, for example, isn’t quite as callous as A&S, and their motives seem mixed — on the one hand they seem to be using manipulative methods to get their way, but on the other they seem to care about broader aspects of the church and its mission. The offender may even be confused and believe their manipulative actions are needed to acquire what they deem worthy spiritual goals for the community. They may not fully appreciate that God cares equally, if not more, about our methods than he does results.

Other times the circumstances are less complex, and it’s more obvious that moral violation through manipulation is happening (even if no one wants to identify it as such). In both cases the response of the church needs to be careful, yet firm. Members of the church need to be help accountable for this type of action, and all the more so if clergy engage in this behaviour, since the stakes are so much higher.

Understanding why we don’t respond

But why does manipulation and abuse of privilege of this sort often go unchecked in the church? One reason might be that we just don’t feel that manipulation of the community of Christ to be all that bad — at least not as bad as other sins. I use the word “feel” here intentionally, meaning that actions comparable to A&S don’t bother our conscience as much as other violations. But I would caution us here that this is due largely to how we’ve been socialized to feel about such matters, and may have little to do with how God feels about them.

Compared, say, to what my own Pentecostal tradition (with its holiness roots) identifies as worth calling out as significant sins — sexual immorality, financial fraud, inebriation from drugs or alcohol, and so forth — the sin of A&S should be right up there at the top of the list. In fact, if God’s reaction is anything to go by, the sin of A&S is worse than drunkenness or getting high, and arguably more significant than many other of the sins that would bring church members and certainly clergy under discipline within my own denomination.

Sometimes the hesitancy to expose and identify this type of sin is due to the idea that this type of behaviour manifests less explicitly than some other sins. It’s just easier to keep manipulation secret or ambiguous than it is a drunken brawl. But what makes identifying this type of sin a challenge, also what makes doing so very necessary. Sin that holds such drastic potential to damage the witness of the community, while at the same time being able to fly under the radar is very dangerous indeed. And just because identifying a particular type of sin may require extra effort or discernment is not a reason to throw up our hands and act as if it didn’t exist. Aside from this, I’m also not as convinced that A&S-type actions are as ambiguous as we might think they are, which leads to the next point.

Another reason that manipulation and abuse of privilege goes unchecked in the church has to do with the way communities operate to preserve their own existence. This includes pressure that encourages loyalty to the community as a moral duty, even when other known moral boundaries are being violated. In those circumstances, loyalty can supersede, say, fairness or justice (on this see Jonathan Haidt’s, The Righteous Mind, and to identify what matters to you most morally, try this test).

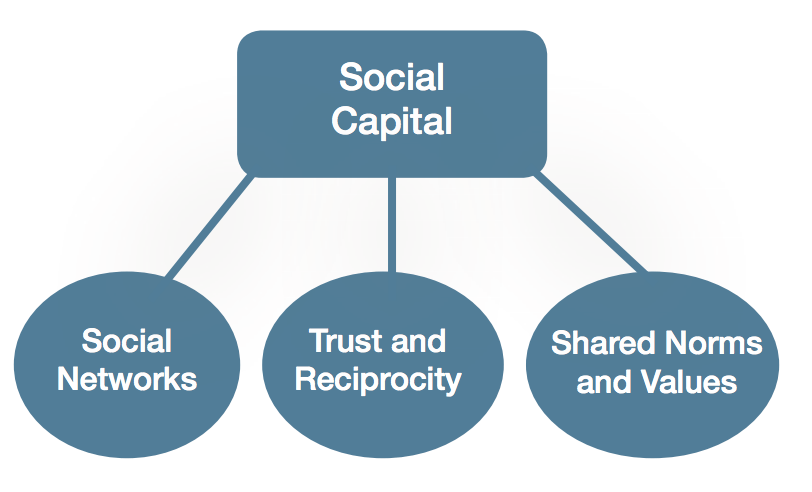

Perhaps, for example, the offending individual already has considerable status and influence in our church. Perhaps he or she has an enchanting and charismatic personality, or comes from a respected family heritage. These features serve to build abundant social capital, which is why such individuals can afford to “spend” (so to speak) some of that capital when using manipulative behaviour, and be fairly confident the community will (should!) tolerate the selfish ambition.

But perhaps the community simply needs the benefactor’s money, and so a blind eye is turned when it cost some communal integrity to receive the money. Or perhaps the cost of calling out manipulative behaviour is just too high. Calling things out can mean loss of significant social capital, especially for a lone whistle-blower (maybe even damaging a career). But perhaps we just don’t want to rock the boat, cause dissension, or be accused of gossip and slander.

Dissension, gossip, and slander are certainly something to avoid, since they too are devilish. But Peter’s response to A&S committed none of those sins. Peter spoke the truth, the truth revealed by the Spirit of truth. His Spirit-led response exposed the true motives of A&S, while at the same time exhibiting what the church community should and should not be.

Peter’s courageous response did not keep the immediate peace. He believed this type of sin required a response that just might rock the boat. But his actions did protect the longer-term peace, integrity, and witness of the church. It kept the devil out of the church, at least for the time being. Luke’s account of this story highlights the importance of calling out this type of sin.

A courageous community

What happened to A&S also, according to Luke, made others think twice about joining the church. Do I really want to live in a community where I can’t use my status, money, and privilege to move my way up and get what I want? I can use those methods pretty much any other social grouping; why would I want to give up that type of power?

The early church, it seems, was not the community for everyone. Well, it was for everyone, but it didn’t operate according to everyone’s preference. But for those with a heart changed by Jesus, it was a community of truth, peace, and joy.

Acts 5:1-11 calls the church to vigilance. A community that exists to represent Jesus’ kingdom values needs to be mindful of the devil’s schemes, including the temptation to use manipulative means to acquire social capital for selfish ends. That community is called to have the courage to refuse to allow that type of behaviour to operate unchecked in Jesus’ church. This was important for the first generation of Christians; it’s important for us today.