I’m just about finished reading (well, listening to) Andy Crouch’s, Playing God: Redeeming the Gift of Power. This is an important read for pastor and church leaders. One element that I really like is that Crouch affirms power as first and foremost a gift from God, and not primarily an evil. He also makes a strong case for institutions being the normal way for power to be multiplied, and for getting things done. Institutions are, therefore, not a necessary evil, but actually a necessary good.

Of course, like any gift in creation, power can be misused; and when power is misused, things go very bad, especially when wielded institutionally. So, all humans, but especially those with designated power or authority, are to grow in our awareness concerning how the gift of power is to be used, and how to avoid the subtle pitfalls that accompany a gift that comes with such potency for good or ill.

Playing god, innocuously

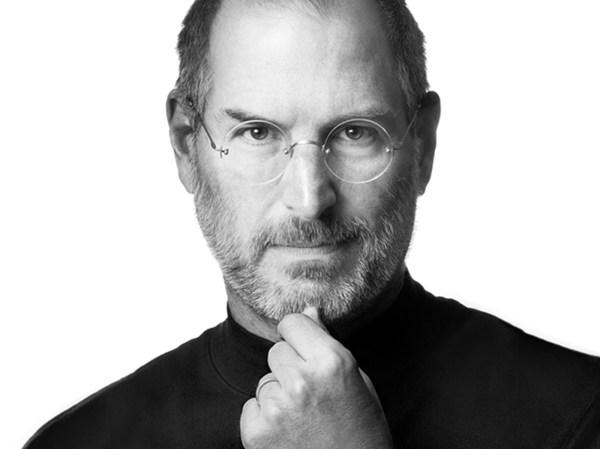

Crouch references Apple creator, the late Steve Jobs, a number of times in the book, as one who wielded tremendous power, formally and informally — sometimes well, other times not. One seemingly innocuous story highlights the latter. The story in brief is this. Jobs ditched a scheduled meeting with his co-workers for a spontaneous date with the woman who was later to become his wife, Laurene Powell. You can read Crouch’s retelling of this account for context, along with some commentary here (on pp. 133-136 of the book). But two comments Crouch makes are especially striking. The first relates to Jobs’ choice to break his obligations (promises) to others to pursue his romantic interests:

But in fact, what Jobs had done was play god, a god whose promises do not matter and, indeed, are ostentatiously broken in order to supercharge a new opportunity with the tantalizing taste of forbidden fruit. It is the stuff romantic dreams are made of: throwing caution to the wind, dropping everything for another glimpse of one’s crush. It is perfectly understandable. And it is saturated with god playing.

So, Jobs’ actions may have seemed trivial, but they reveal a willingness to overstep boundaries, especially when the right to do so is assumed. This is “god playing,” and we, like Jobs, also like to play god.

Second, rather than call each other on this power over-step, we not only ignore, but culturally have often spun this type of disregard of promises into a virtue of sorts. Crouch explains:

Yet this is exactly the sort of story we tell all too often about our heroes—or, better put, our idols—stories of breaking the rules in order to get the girl, bending the truth to serve some great cause, committing crimes in order to achieve justice. False god players believe that to have what we really need and want, we have to break our promises. We believe this, as Jobs’s choices that night show, even when it is patently not true.

Giving misuse of power a pass

Crouch goes on to say that we may tend to give creative, entrepreneurial people like Jobs a pass for their narcissism and misuse (sometimes outright abuse) of power because of the results they achieve. In other words, we all too frequently assume abuse of power is necessary in order for a person to fully exercise their creativity in a maximal beneficial way. Isn’t this, after all, what enabled Jobs to achieve what he did? This type of thinking is true, by the way, both outside and inside the church (and it is idolatry, “false god playing,” in both contexts). Crouch argues that this assumption is dead wrong. He states:

Of course, the opposite is closer to the truth. It is not those who keep their promises who end up bereft, but those who have been seduced into god playing.

Abuse of power never, then, ultimately brings about maximal human flourishing for group or individual.

I’m not as concerned as much here with what happens outside the church world as inside it, although both realms are important. But since within the church we have at least in principle declared that our allegiance is to Jesus, it is a very serious matter when idols of power (i.e., misuse/abuse of power) are allowed to operate unidentified and unchecked, or worse yet, celebrated as a necessary part of the “entrepreneurial” or “creative spirit.”

What do you think?

So, what do you think? Do creativity and entrepreneurship necessitate that we (ought to) look the other way when abuse of power is evident (even when the abusers are getting results)? Or is Crouch right, that the best expression of creativity and entrepreneurship, for both the creative individual and the masses, is that which works towards allowing others to also exercise their power as agents made in God’s image? And if Crouch is right, how might this change the way we handle “false god playing” in the church world?